Blogue

Jetting of towards planes… without pilots

The Falcon 10X business jet from French manufacturer Dassault is one of many new models that incorporate touch screens in the cockpit. The delivery of Dassault’s first planes is scheduled for 2025. (Photo : Dassault Aviation)

In his Polytechnique Montréal laboratory, Philippe Doyon-Poulin and his team are outfitting tomorrow's cockpits, where screen-lined interiors gradually transform the pilot from a driver... to a supervisor.

In the early days of civil aviation, large carrier aircraft cockpits could accommodate up to five crew members, each fulfilling a specific role: navigation, piloting, fuel monitoring, communication and in-flight passenger safety.

With aircraft technological improvements, this number decreased, and from five, went to four, then to three cockpit crew. Since the 1980s, aircraft have been certified with two pilots performing all flight tasks and ensuring passenger safety. This certification means that if one of the pilots were to lose consciousness or become incapacitated in-flight, the second pilot would be able to land the aircraft safely on their own.

Philippe Doyon-Poulin, a specialist in cockpit ergonomics and Assistant Professor in the Department of Mathematics and Industrial Engineering (MAGI) at Polytechnique Montréal, is already looking further ahead. "Now the target is to certify aircraft flight with a single pilot. For that to happen, these planes have to be capable of flying without a pilot," explains Doyon-Poulin.

From pilot to supervisor

Professor Philippe Doyon-Poulin (Photo : Polytechnique Montréal) Professor Philippe Doyon-Poulin (Photo : Polytechnique Montréal) |

Let me reassure you right away: ground-based pilots already control military drones, but the era of ground-based pilots controlling commercial flights is not yet upon us. All this is a possibility now because aircraft cockpits have gone digital - just like so many other the tools around us. Once lined with buttons and manual controls, cockpits these days have touch screens used for part of piloting operations.

“The pilot's task is changing,” says Professor Doyon-Poulin. “Instead of being a driver, pilots are increasingly becoming automated systems supervisors who must be able to intervene quickly when there's a problem."

This sort of cockpit transformation forces engineers to rethink layout; its also something that inspires many questions. Can we interact with these tools safely? Which controls should remain under mechanical or electrical control? What happens if a screen fails, or if the aircraft goes through extreme turbulence?

Professor Doyon-Poulin's research group is trying to answer some of these questions by ensuring that the new pilot interface remains safe and easy to use. Trained in cognitive engineering and ergonomics, Doyon-Poulin worked in aeronautics at Bombardier, sharing flight simulator classes with real pilots for over 700 hours, and for certification tests. In addition to assessing pilots' concentration levels at various stages of a flight, he ensured that the screens they used were easy to employ, and prevented human error risks.

"I became good at my job when I understood how pilots think and use the cockpit in complicated flight scenarios," he confides. "I learned a lot by watching and questioning them during my time in the simulator. Those are the most informative moments in my particular disciplin, and that's what I tell my students: go out in the field and watch the operators do their jobs. Then you can come back with a wealth of information that you never would have known if you'd simply read technical specification documents."

When engineering... and ergonomics meet |

|

POLY magazine's August edition featured an article on Professor Doyon-Poulin's research group, who notably evaluated various means by which a pilot could interact with touch screens in a homemade cockpit capable of simulating turbulence. Is it easier to transmit commands by stretching out your arm to touch the screen with your finger, or should you use a keyboard or trackball closer to your body? The question may seem trivial, but you don't skimp on the safety of an airplane flying through turbulence. "Making a mistake in a text message is not so serious, but when it comes to navigation coordinates, it's a different matter," he notes. In addition to the constraints of safety and ease of use, there's also the factor of space available on-board. “Space is a rare commodity in the cockpit, so we're looking to maximize use of space, while also allowing the pilot to have access to as much information as possible," explains Professor Doyon-Poulin. So what of the project lead by the professor's master's student Adam Schachner? Pilots are twice as fast when interacting directly with a screen rather than interacting through a cursor. But, their error rate is also higher, around 10-15%. Unsurprisingly, the error rate jumps to 30-40% during periods of vibration when on-screen targets are small (about 8 millimeters in diameter, the smallest size objects presented to pilots). Consider ads that appear on your cell phone screens - you try to erase or hide them by selecting a tiny X.... pilots face the same sort of visual challenge. |

From the cockpit to the factory

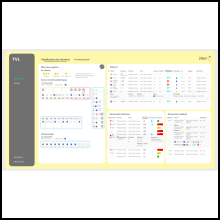

Once completed, this new user interface from a chemical plant simulator will facilitate operator decision-making by offering an AI-based solution process during a series of alarms. (Photo : Karine Ung) Once completed, this new user interface from a chemical plant simulator will facilitate operator decision-making by offering an AI-based solution process during a series of alarms. (Photo : Karine Ung) |

Outfitting the cockpits of the future is not the only interest of the members of the MAGI Department team at Polytechnique Montréal.

“Our primary objective is to facilitate critical decision-making in complex environments, whether the operator is an airplane pilot, a plant operator or medical personnel,” explains Professor Doyon-Poulin.

Doyon-Poulin also supervises other intersting projects, for example, doctoral student Karine Ung who also works under the co-supervision of Assistant Professor Moncef Chioua in the chemical engineering department.

Their objective? To adapt the simulator of a chemical plant to offer the human operator possible solutions when several alarms are triggered at the same time, a phenomenon commonly called a “flood of alarms.”

Just like in an airplane, alarms are triggered when a measurement reaches a level that should not be exceeded, or when a sensor fails. According to Professor Poulin-Doyon, several alarm signals often appear at the same time. An example? The loss of electrical power. This triggers an alarm directly related to the loss of power, which is the cause of the problem, but also a range of alarms associated with equipment that has lost its power supply and is now inoperable.

"It becomes very difficult for the operator to identify the cause of the problem," he says. "In aviation, if there are 15 alarms, then the pilot has to perform 15 procedures one after another - when in reality, the problem may have only one source. The situation is the same in the chemical field, which is why this project is so interesting."

The group wants to facilitate decision support by offering the operator the most likely cause of the problem from the amoung the numerous alarms present, so the problem can be resolved as quickly as possible. A diagnostic tool based on an artificial intelligence algorithm, will guide the operator to speed up problem resolution in the virtual plant.

Learn more

Professor Philippe Doyon-Poulin expertise

Professor Moncef Chioua expertise

Departement of Mathematics and Industrial Engineering website

Departement of Chemical Engineering website

Comments

Commenter

* champs obligatoire